This chapter and the next are meant for readers who are interested in music but have no basic knowledge and skills in Western music. So, if you are an expert in Western music, ignore both.

The rudiments are limited to the musical elements Dr. Kunst explained in his book on traditional music in Netherlands New Guinea. In such a way, you are expected to understand easily Kunst's discussions of Papuan traditional music in the coming writings. You can use both chapters as your references if the technical analysis of Kunst is not so clear or rather puzzling to you.

Elements of Western Music

GENERAL ELEMENTS

There are four general elements of Western music. First, rhythm (and meter); second, atmosphere; third, mood; and, fourth, message.

Rhythm and meter

The rhythm in popular or contemporary music is called style, tradition, idiom, or genre. In modern popular music, rhythm includes country, folk, waltz, rock 'n roll, samba, salsa, disco, and other kinds of styles. Rhythm also includes the fusion of various pop genres such as country-rock, jazz-rock, and Latin-disco.

Those who can play the rhythm guitar know that playing, for example, a country rhythm is different from playing a salsa rhythm. The strumming patterns of your guitar for the first kind of idiom is different from the ones for the second style. In a rhythmic notation, a special notation for the rhythm guitar, each tradition is described with patterns of note combinations of various values.

In music, rhythm is a part of a melody. The rhythm is related to the distribution of notes in time and the accents on notes. The notes in time are given various values.

For example, in a musical piece of four beats in a bar, a note having the value of four beats is played a bit longer (say, for four seconds) while one note having the value of one beat needs a shorter period of time to be played (for example, for half a second). Another note for half a beat clearly needs a much shorter period of time to be played or sung.

In addition, not all notes get the same accents. Some notes get strong accents, others get relatively strong accents, and the rest get weak accents.

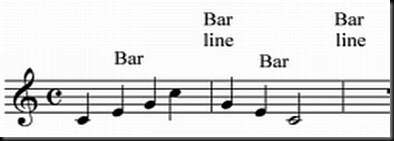

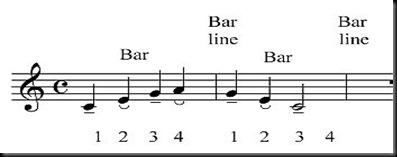

In a song of four beats in a bar, the four notes that correspond to the four beats in a bar are restricted by two straight lines on their left and right sides. Each straight line is called a bar line and both lines form a bar (termed maat in Dutch but spelled and pronounced as mat in Indonesian). The unity of the four notes that have the same value as the four beats form the first bar. Though the second bar indicates four beats, only the first two notes correspond with the first two beats. The third note that includes two counts tallies with the other two beats in the same bar. There is clearly no one-to-one correspondence between the changing note values and the consistent beats or meter in a bar.

According to standard rules, the first quarter note that corresponds to the first beat in a four-beat bar gets a strong accent. Each quarter note that tallies with the third beat gets a relatively strong accent, and each note that has the same metrical value as each beat in the second and four counts in a bar is given a weak accent.

Two different signs are used to indicate the different kinds of accents. The dash (-) represents both the strong and relatively strong accents on notes. The crescent-like sign or curvy line indicates weak accents in a four-beat bar. The half note in the second bar, however, gets a strong accent because it has two counts or beats: beats three and four. When two beats of a 4/4 time-signature score are represented by a half note, the half note gets a strong accent.

Related to the research on Papuan traditional music in Dutch New Guinea is the term "free rhythm" that you also need to know. It is a kind of rhythm not determined by the regular occurrences of bar lines but by the occurrences of the natural or conventional flow of notes. A melody or song that uses free rhythm will virtually involve change of time signatures - some are uncommon - which can be more than twice. For instance, a song can begin with an odd meter such as 7/4 and then changes into 2/4, then 4/4, and ends with 7/4.

In Indonesia, you can scrutinize free rhythm in psalms published in two widely used hymn books in Indonesian for Christian services (mostly, for main-stream Protestants and Catholics). The first one, Mazmur dan Nyanyian Rohani (Psalms and Spiritual Songs), was a compilation and translation into Indonesian of various hymns from Europe, Britain, and the USA by Rev. I. S. Kijne (1899-1970). He is an important and famous Dutch missionary of the Dutch Reformed Church who worked in Netherlands New Guinea from 1923 to 1958. The second, Kidung Jemaat (Songs for the Congregation), was published by the Institute of Sacred Music in Jakarta that has involved professional musicians from Indonesia and abroad in an ecumenical cooperation between main-stream Protestants and Catholics.

The free rhythm is not only evident in the psalms in both song books. (The psalms were translated from Genevan Psalms of the 16th century into Indonesian in the 2oth century.) You can also observe it in the Gregorian chants sung in Catholic services.

Rhythm, however, is different from meter. Whereas rhythm deals with the distribution of notes in time and their accentuation, meter, simply said, is a grouping of basic and permanent beats of a song or melody.

In popular music, meter is known as beat. Different meters form different time signatures, such as 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, 6/4, 3/8, 6/8, and 12/8. The figure on the left of the slash indicates the number of beats in one bar; the other figure shows the basic note value that underlies various note values that shape the rhythm of a melody.

Popular music styles are abundant with examples of meters. The energetic four-beat disco music demonstrates its meter through the regular sounds of its bass drum: DUM DUM DUM DUM.

Atmosphere

The term "atmosphere" refers to the environment of a song. It answers the question: Where are you: at a tropic beach, a snowy mountain top, a church, home, or a hotel?

Mood

What are your feelings behind what you are singing to us, your listeners? Are you happy, contemplative, peaceful, calm, respectful, lonely, playful, expressing a yearning?

Message

What do you, a singer, tell us, your listeners? What are your facts, viewpoints, and philosophy; what kinds of responses do you expect from us?

SPECIFIC ELEMENTS

Besides the four general elements, Western music also consists of for specific elements. First, lyrics; second, melody; third, harmony ; and, fourth, rhythm.

Lyrics

These are the words of a song. A message is different from lyrics. A message is what you say through a song or melody; lyrics are how you convey your message through your song.

Lyrics express emotions in general. Songs - that include melodies and lyrics - are expressive, lyrical. Lyrics can consist of verses and choruses. A verse shows, a chorus tells. A verse shows someone or something through a specific and an interesting language; a chorus tells us something through a comment or a summary of the verse.

Melody

This element is a combination of a series of pitches and rhythm. The series of pitches and rhythm are denoted by a series of notes and rests with various values. Harmony - the combination of two, three, four tones or more based on certain rules - and lyrics are other parts of a melody and are used as needed.

Intervals and scales

The series of notes in a melody are formed by intervals. An interval is "the distance" between two notes, as far as one is higher or lower in its pitch than the other. For example, the distance between the doh and ray or the other way round step-wisely forms the second interval because you sound two notes up and down. The third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth intervals are respectively doh-me (there are three notes, doh-ray-me); doh-fah (there are four notes, doh-ray-me-fah); doh-soh; doh-lah; doh-te; and doh-doh (the second doh is eight tones higher than the first). In addition, there are intervals larger than an octave, such as the ninth interval (doh-ray with ray as the ninth note above doh); the tenth interval (doh-me with me as the tenth note above doh); the eleventh interval (doh-fah with fah as the eleventh note above doh); and other intervals larger than the eleventh.

There are also intervals based on two notes with the same pitch - so, their tones are the same. Because they involve just one tone, they are called the first intervals, such as doh-doh, ray-ray, me-me, fah-fah, soh-soh, and so on.

Diatonic scale

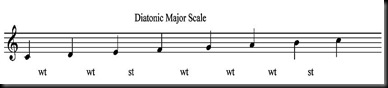

The characteristics of intervals also depend on scales. The examples of intervals already mentioned belong to a Western scale commonly used for composing songs: the diatonic major scale.

Notes: wt=whole tone; st=semitone

All those examples of intervals based on diatonic major scales have tone distances. The tones in these scales are main or basic tones. Each pair of the most adjacent and step-wise notes have a whole tone except the semitone between me-fah and te-doh.

The diatonic major scale is usually used to compose happy, cheerful, "bright" songs - in short, songs that express optimism. There are also sad-sounding songs composed in the diatonic major scale. Listen to folk songs or classical pop songs from Ambon, the Moluccas, in the eastern part of Indonesia. Sentimental or mellow songs with slow tempo such as Nusaniwe and Sioh, Mamae composed in the diatonic major scale can be so moving that they make some listeners cry.

Chromatic scale

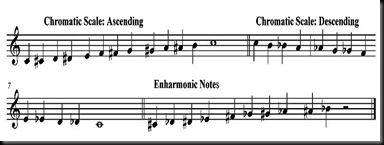

Because the diatonic major scale has two whole tones, arithmetically, the tone distances of note pairs having whole tones can be divided into two. The note pairs doh-ray, ray-me, fah-soh, soh-lah, and lah-te that respectively have whole tones as a result are divided into semitones. A new scale in which each note pair is equally divided into semitones is created.

The new scale is termed the chromatic scale. From the lowest to the highest sounding tones, the note sequence of the chromatic scale, both ascending and descending, is as follows:

In its ascent and descent, the new scale shows specific signs that identify the semitones. A sharp (#) is used to indicate a semitone in the ascending direction of the scale; a flat (b) is used to show a semitone in the descending direction of the scale.

Practically, the semitones in the ascending and descending directions of the chromatic scale sound the same. To be specific, the raised doh, ray, fah, soh, and lah respectively sound exactly the same as the lowered ray, me, soh, lah, and te. The identically sounding semitones in the chromatic scale are called enharmonic notes.

Songs composed in the chromatic scale give more emotional "colors". They sound subtle when they are used in harmony.

Minor scale

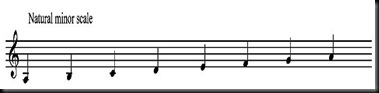

A third type of Western scale usually used for composing sad, melancholy, depressed, contemplative songs - in short, songs for introspection - is termed the minor scale. This scale is divided into three sub-types. First, the natural minor scale. The one of C has the following notes:

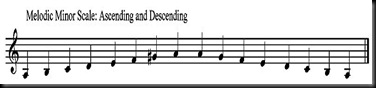

You can also play this scale from the highest to the lowest sounding notes. Second, the melodic minor scale. The notes in its ascent are slightly different from those in its descent.

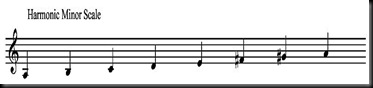

Third, the harmonic minor scale of C in its ascending direction uses these notes:

The scale can also be played downwards, using the downward movement of that of the melodic minor scale.

There are songs composed in the minor scales, but they have cheerful atmosphere and mood. These include some religious songs from Israel and dangdut songs from Indonesia. These types of songs, however, are not common.

(Dangdut is a type of popular music in Indonesia. It has strong beats that are reminiscent of Hindi and Arabic music. It is also a type of dance to such music.)

Specific interval combinations

The typical rhythmic patterns of a melody in any of the scales already explained are formed by the combinations of various intervals. In vocal music (the combination of singing and musical accompaniment), the patterns are influenced by the rhythm and meaning of its lyrics. Sustained notes - for instance, for two to four counts in a four-beat song - are appropriate for emphasizing an important lyrical message, such as the title of a song. Pairs or groups of quick-moving eighth and sixteenth notes are suitable for songs that sound like conversations. The rhythmic patterns indicated by various flags of notes with small values express the mood of activity that needs high energy such as busy work, hustle and bustle, sports competitions such as soccer competitions, and even chaotic situations or wars.

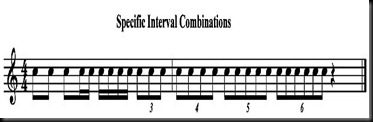

There is still another technique for combining various notes to form some other rhythmic patterns. Three consecutive notes - not necessarily of the same pitch - are combined by a straight line having 3 written over it - a triplet. Four consecutive notes are also combined by a straight line having 4 written over it - a quadruplet. Five consecutive notes connected by another straight line with 5 written over it form a quintuplet. A group of six notes with equal time-value which are combined by a straight line with 6 written over it is called a sextuplet. Each specific combination of notes just explained is counted as one beat, for example, in a four-beat song.

The following example contains all specific combinations of intervals already explained:

Typical rhythmic patterns

In world popular music, typical rhythmic patterns of melodies can indicate origin and can even increase the "selling values" of songs. Compare, for instance, typical popular music from mainland Europe, Britain, and the United States that uses idioms such as waltz, country, and rock 'n roll with that of the Caribbean Sea such as reggae from Jamaica and bolero from Cuba and also with that of Latin America such as samba and salsa. You will listen to typical rhythmic patterns that may be difficult for you to explain from these areas but which you can really feel - and love so much that you buy their cassettes or CDs. These rhythmic patterns are affected among others by the rhythm and meaning of song lyrics in the languages of those areas and also by the typical combinations of various intervals and their note values.

The rhythmic patterns resulting from the combinations of various intervals and their values can evoke various moods. Combinations of small and relatively small intervals such as the first, second, and third intervals express calm and relatively calm songs. Combinations of the fourth, fifth, sixth, and other larger intervals produce dramatic, prominent moods. The note sequences can be from the lowest to the highest sounding or vice versa.

0 komentar:

Posting Komentar