The Sudirman Mountain Range in the present-day Papua was called the Nassau Mountain Range in the former Netherlands New Guinea. It includes the western snowy mountain range and a part of the central range that sticks out to the west of Dutch New Guinea, from the Balim Valley to the Weyland Mountain Range, more or less behind the present-day region called Nabire, the southern part of the Cenderawasih Bay.

The Papuan tribes living in the Nassau Range bartered with other Papuan tribes living in the high lands with lakes in van Rees Mountain Range for various commodities. This range is located in the hinterland of Waropen, west of the Mamberamo River.

The tribes in the van Rees Mountain Range used sacred flutes while those in Nassau Range used the jewish harps. The harp was apparently used in the whole of Dutch New Guinea. Different from the most primitive music of the Kauwerawets, the music of both tribal groups contains typically detailed songs.

Songs of the Uringup Tribe

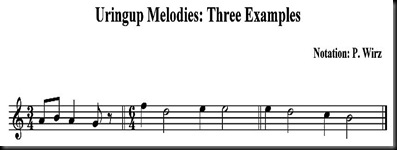

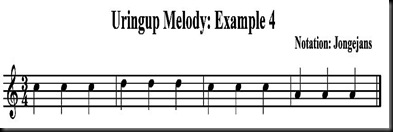

The songs belong to the Uringup tribe which lives in the Swart Valley. The valley is located near the Swart River, one of the tributaries of the Mamberamo, the largest and longest river in Netherlands New Guinea, that flows from the Balim Valley. The songs were studied by J. Jongejans, a Dutch government officer, and were published in 1921, and also by Dr. P. Wirz, a Swiss ethnographer. Wirz's study was first published in German in 1924 and republished in English in Amsterdam, Holland, in 1952.

A large number of melodic phrases of the tribe shows a very primitive characteristic. Generally, their ranges do not exceed the fourth interval. Based on Dutch musical tradition, Dr. J. Kunst who listened to those phrases said the songs reminded him of "Dutch nursery rhymes and ditties".

Dr. Wirz gave three and Jongejans gave three other examples of the Uringup melodies. Each example is limited by double bar lines.

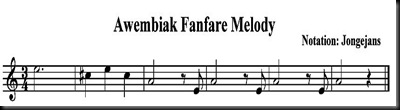

However, another fragment noted down by Jongejans is based on a song of the Awembiak tribe that differs much from other phrases:

Triad and Fanfare Songs

That fanfare melodic phrase reminds Kunst of a Western military signal. Such a short tune is usually played on a bugle or trumpet to wake soldiers in the morning, to call them for morning assembly, or to call them for raising or hauling down their national flag.

The impression of the similarity between the melodic phrase and military signal is strengthened by a number of songs and song fragments collected from the Awembiak and Dem tribes by Le Roux and Muhammad Saleh, his assistant. Both hinterland tribes are related to the Uringups and live in the mountainous area near the present-day Enarotali.

However, the fragments sung by the Awembiaks were noted down only by listening to them. Such notation method is feared to have neglected the curious or exotic intervals of the Awembiak original melodies. Neglecting such intervals happens if the way the melodies of remote tribes noted down tends to be affected by modern music.

In spite of this, there is a way for confirming whether the notations of the Awembiak and Dem melodies are accurate or not. They can be compared with similar melodies also noted down of other Papuan tribes in New Guinea. Such a comparison is meant to cross check the noted accuracy of the melodies.

Kunst then rewrote the songs sung by the Awembiaks as they were sung and whistled by Le Roux and played on the violin by Muhammad Saleh after they returned to Batavia. Those songs reminded Kunst of a type of Western music called "fanfare music". It is a flourish for trumpets (or other instruments imitating them), usually for celebrating somebody or something important arriving; it is sometimes used in the compositions of some Western classical music. In modern Western pop music, fanfare music is called brass band.

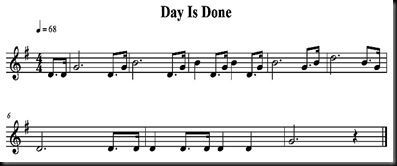

The fanfare melody in Western military or modern music is formed from three basic notes. In the key of C major, they are C, E, G or other notes - such as F, A, C - and their inversions. The three basic notes and their inversions are artistically manipulated by involving typical rhythmic and pitch patterns.

Other terms that denote fanfare music include reveille, trumpet call, or bugle call. Day is Done is an example of Western fanfare music; the melody basically uses triads.

Not all songs that use the three basic notes can be called fanfare songs. They show typical characteristics.

Kunst characterized the fanfare melodies of the Awembiaks that he noted from Le Roux and Saleh "flourished triad" melodies. The melodies are, therefore, formed from triads - and their inversions - that are short and loud.

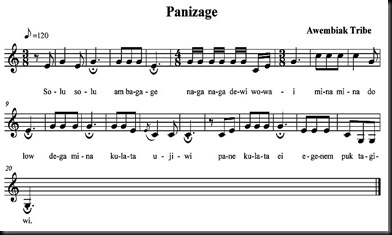

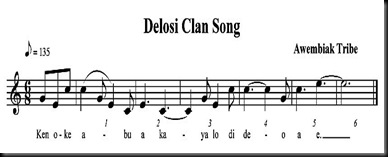

You can observe two different fanfare songs of the Awembiaks. The first, Panizage, uses two different time signatures: 3/8 and 4/8. The second, a 6/8 song, is sung by the Delosi clan of the Ndani family group. No translations of the texts of both songs are available.

What about the fanfare songs of the Dem tribe? They are very interesting because they remind Western musical ears of antiphones. The word "antiphone" is derived from the ancient Greek word antiphon which means "sounding across". The term is used in Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox church services to describe songs sung as responses between single and many voices or between two groups of singers. The noun phrase antiphonal singing means singing whose effects are drawn from the use of groups of performers stationed apart.

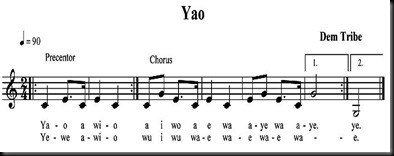

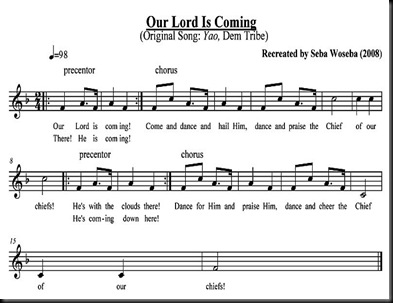

In the case of the Dem singers, their singing of fanfare songs is antiphonal in the sense that it involves a solo singer and a choir. The solo singer sings a part of the melody followed by the choir that includes the solo singer. All of them sing in unison.

Such singing must have reminded Dr. J. Kunst of antiphonal singing in Anglican Church services. He termed the part of a song sung by a solo singer "precentor" and the part sung by a choir "chorus". A precentor in an Anglican cathedral is a musical dignitary, a cleric in charge of the vocal music and technically leads the organist. In other words, a precentor has some general control on the songs in an Anglican Church service. In relation to the singing technique of the Dem singers, Kunst uses the term "precentor" to refer to the solo singer; he, in turn, has some general control on the group singing.

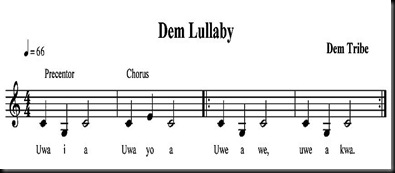

Two Dem songs that involve a precentor and a choir sound like modern Western songs. Yao is the first and the second is a lullaby. Both are triadic songs that uses fanfare melodies.

The word aye means ancestors.

Precentor and Chorus

A Dem song that consists of a precentor and a chorus is actually not unique of the Dem tribe. This characteristic is also found in the songs of some other tribes in Netherlands New Guinea and in some modern songs.

The rano, a traditional row song of the people in the coastal Yapen-Waropen and the wor, a collective name for various traditional songs some of which are for dancing in Biak-Numfor, are basically antiphonal. A solo singer who starts a song is joined later on by a choir. (The rano and wor will be discussed separately in some chapters.)

Antiphonal singing is used in modern pop songs and in church songs. In modern pop songs, it can be heard from some songs of Harry Belafonte, a New York-born Jamaican singer of the 1950s and 1960s. In The Banana Boat Song, one of his famous songs, he sings the solo part and a choir enters the refrain or melodic repetition that has the words Daylight come and me wan' go home. This singing technique is also noticeable in hymns or songs for Christian church services, including those of the Catholics.

Antiphonal singing, the use of a precentor and chorus, is obviously nothing new in modern music, secular and spiritual. Its origin can be traced back to traditional antiphonal singing in the past.

The Origin of Fanfare Music

Where does the Awembiak fanfare music with its flourished triads come from? It is not easy for Kunst to answer this question. The info he needs to answer it either does not exist, is inadequate, or is less adequate. The influence of traditional music from the coastal Papuans in the northern coasts of Netherlands New Guinea is hard to be determined because, to a certain extent, their music has been influenced by the music from what is nowadays known as the Indonesian Archipelago.

This foreign source is more apparent in the southwestern coast of Netherlands New Guinea through the musical elements, particularly, from Tidore and Ternate in North Moluccas. This origin is noticeable from the musical instruments - the rebab ( a two-stringed musical instrument), tambourine, gong, and Malay tifa (the cylindrical drum) - played by coastal Papuans in the southwestern coast of Netherlands New Guinea.

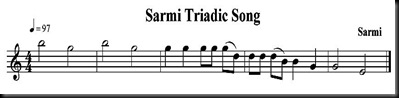

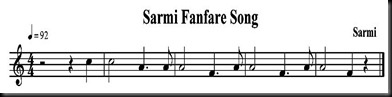

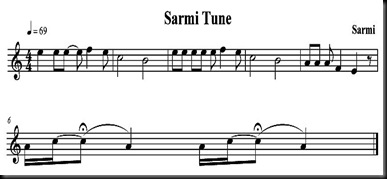

The inspiration from traditional music from the Indonesian Archipelago in the old days is not only apparent in the traditional music of the Papuans in the southwestern coast. It has also existed side by side with the Australian aborigine type of music in Sarmi, a coastal area near the Mamberamo estuary some hundred miles west of the present-day Jayapura. From the various collections of songs from Sarmi, J. Kunst discovered both the Australian aborigine type of music and music inspired by traditional Indonesian music.

A song from the musical layer of the Australian type in Sarmi indicates triadic but with no fanfare characteristics.

There is, however, another Sarmi song of the fanfare type.

Kunst's collections include a song from Sarmi that has probably been influenced by traditional music from the Indonesian Archipelago. This short song is melodious but slightly droopy.

The Aborigine and Indonesian Types of Music

The influences of the Australian aborigine type of music in Kauwerawet songs and of the traditional Indonesian music in that Sarmi song are also found in the traditional music of Yapen, Waropen Coast, and Humboldt Bay. Kunst noticed these from the recording of the singers from these areas in the Ethnographic Exhibition in Batavia in 1929. The Yapen songs show an affinity with those of the Kauwerawets. The Humboldt Bay songs, however, are more varied; they are not fanfare songs but songs still related to the Australian type of songs. In contrast, various songs from the Waropen Coast seem to have been affected by Indonesian traditional music of the past centuries. This effect can be noticed from what Kunst termed the "pelog character" in the Waropen songs in which semitone or second minor intervals are frequently audible.

Another Waropen song is prominently triadic but is not of the fanfare type. It has a range of one octave.

Other Characteristics

A festal song from Sarmi, however, has a range of more than one octave because it has twelve tones. The song is beautiful and contains some variations; its melodic range is the same as that of Panizage of the Awembiaks.

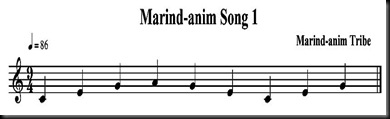

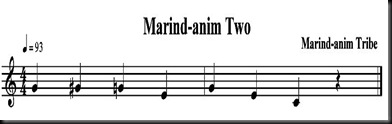

Talking about intervals in songs, some song fragments from the Marind-anim tribe in the southern coast of Dutch New Guinea tend to use the third intervals and, occasionally, triads. These songs are short, like those of the Dem tribe. The Marind-anim songs, however, are not fanfare songs.

Two fragments are given here:

A slightly longer and more varied melody was noted down by Kunst from a song sung by an adult male from the Kaoh River, Upper Digul, in the southern part of Dutch New Guinea. The man accompanied Dr. de Rook, a Dutch scholar, to Bandung, West Java.

Rallentando and a Tempo

Interestingly, the temporary slowing down and return to the normal tempo applied twice by the Papuan singer are indicated by the two musical terms Kunst used: rallentando (slowing down of the tempo) and a tempo (return to the normal tempo). Both enhance the expressive power of the song and indicate that the rallentando and a tempo techniques also exist in traditional music in Dutch New Guinea.

Summing-Up

The musical culture of the Kauwerawet and Uringup tribes which is the most primitive belongs to the Australian aborigine type of music. This type of music is also discovered among certain songs of the coastal Papuans living in Sarmi, Yapen, and Humboldt Bay. The primitive level of their musical culture forms a part of the original Papuan music.

The songs discussed so far use different time signatures. There are songs that are controlled by one type of time signature. It includes 2/4 (Yao); 3/4 (the Uringup melody and Awembiak fanfare melody); 4/4 (the Dem lullaby song, the songs from Sarmi, and the second song from Marind-anim); 6/4 (the last two melodies of the Uringups); 9/4 (the first Marind-anim song); and 6/8 (the song of the Delosi clan). There are also songs controlled by more than one type of time signature, such as Panizage (3/8, 4/8, 3/8); and the Upper Digul song (9/8, 6/8, 9/8, 6/8). Such change of time signatures shows that the melodic motion is freer; besides, the beats and rhythmic patterns of the songs change.

The higher level of musical culture in Netherlands New Guinea is noticeable from the Awembiak and Dem songs in the high lands and from those of some other tribes. The Awembiak songs involve triadic fanfares, a form also found in Dem songs. Triadic but non-fanfare songs are also found in Sarmi and the Waropen Coast.

The higher level of musical culture in Dutch New Guinea has six characteristics:

- The melodic motion is varied. Different from the most primitive traditional songs that start with the highest and end with the lowest tones, the more developed songs tend to be short, slightly short, or slightly long. The short ones tend to ascend and descend the scales, like the Awembiak fanfare melody, the Dem lullaby, and the two Marind-anim melodies. The slightly short songs use higher tones at the beginning and tend to descend the scale, such as the Upper Digul song. The slightly long songs, such as Panizage, move up and down and then descend the scales at the end.

- The singing techniques that include a solo singer and choir in Dem songs show musical development that is higher than those of the Australian type of songs. The application of precentor and chorus seems to affect the composition of the triadic melodies through inversions.

- The influence of traditional music from the Indonesian Archipelago, particularly, from Tidore and Ternate in North Moluccas is evident from the musical instruments - the rebab, tambourine, gong, and cylindrical drum - used among the coastal Papuans of southwestern Netherlands New Guinea. This foreign element has also influenced the melodic structure of a song from Sarmi and another of pelog character of a song from the Waropen Coast.

- The triadic and fanfare songs of the Awembiak and Dem tribes and the varied motion of their melodies indicate a level of musical culture that is higher than that of the aborigine type of musical culture in Dutch New Guinea. This level reminded Kunst of the triadic and fanfare music in the West, a thought association that implies his identification of another level of musical culture in Dutch New Guinea.

- The identification of rallentando and a tempo in the Upper Digul song on the basis of Western music shows a new level of development of traditional music in Dutch New Guinea discussed so far. Both terms that are related to tempo nuances indicate that tempo nuances are also found in the traditional music of Dutch New Guinea.

- The broader ranges of twelve tones in a festal song from Sarmi and of Panizage tell us of a higher development of vocal music in Dutch New Guinea. The twelve-tone festal song from Sarmi shows one extra tone compared with the famous Christmas hymn, Silent Night, whose main melody has eleven tones.

Modernizing Traditional Songs

Singing or playing traditional Papuan music as it really is will not help anyone to develop it. The modern musical ears even of the conservative Papuans of the 21st century have made them foreigners, strangers to the music of their ancestors. It is only through developing or modernizing Papuan music that those concerned with its "survival" can popularize it to a wider audience.

One of the challenges to be overcome is to popularize transformed or renewed traditional Papuan music without ignoring its characteristics, including its typical imagery. Overcoming this challenge means strengthening the cultural identity of the Papuans through music.

The texts (words or lyrics) of almost all the traditional Papuan songs discussed so far are not translated into Dutch or English. These include the texts of the triadic fanfare songs of the Dem tribe. Consequently, the whole meaning, functions, or roles of these songs in both tribes are not known. For example, it is not known whether the triadic fanfare songs of the Dem tribe have the same role as the Western triadic fanfare songs, such as announcing or celebrating important people or events that are arriving. If they have different roles, what are they?

Lacking the knowledge and understanding of such roles makes it hard for concerned musicians to modernize Dem triadic fanfare songs. Assuming that both the text and the melody of a Dem song work together to convey a main message that fulfills its role, then modernizing it has to take these prosody and role into consideration. Unfortunately, nothing is known about both.

A modern musician who wants to modernize a Dem song is only left with its melody. How should he modernize the text on the basis of the original words of the song that he does not understand? What should he do if he is not able to ask a present-day member of the Dem tribe to translate the text for him?

A possible solution for him is to establish a musical bridge between the old and new music he recreates. He can modernize the melody without neglecting its characteristics, for example, by adding some measures and its tempo, modifying or rearranging some notation patterns, harmonizing it, using local imagery, and using modern musical accompaniment. In addition, he can add a new text that fulfills the role of a modern fanfare song, such as the announcement of an important person who is arriving. Such musical communication is expected to be appreciated by both the traditional and modern musicians and listeners.

It is on such reasoning that Seba Woseba, a Papuan musician, ventured to recreate the Yao song of the Dem tribe. He did not change its original melody that includes its precentor and chorus but extended its measure by adding three notes of the same pitch as the last. To give it a modern feel, he determined its new tempo, new key and time signatures, harmonized it in four parts, and used some wind instruments (the trumpet, trombone, and tuba) and percussion to arrange its musical accompaniment. He also added a new text that fulfills its modern role: to announce or celebrate the second coming of the biblical King of kings.

This biblical image, however, is foreign to the Papuan tribes in the hinterland. They do not know kings but tribal chiefs. An analogous phrase of that biblical image the tribes will understand better is "the Chief of (our) chiefs". In addition, their music consists of solo and choir singing, dancing, and occasional yells, such as yells of delight and "jungle yells".

The extended main melody, tempo, and words of the modernized Yao is given below. The text reveals typical imagery of the mountainous Papuans. The complete instrumental melody can be listened to by clicking it at the side bar of this blog.

0 komentar:

Posting Komentar