What are other characteristics of the Central Range songs in Netherlands New Guinea, as analyzed by J. Kunst? The characteristics include those of melodies and lyrics studied in the music of the Kauwerawets, Mamberamo Papuans, and pygmy tribes in the Swart Valley. For wider understanding, Kunst compares the music of these tribes with that found along the coasts of Dutch New Guinea, in Papua New Guinea, and in the eastern part of Asia.

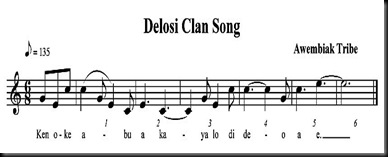

Characteristics of the Kauwerawet and Awembiak Songs

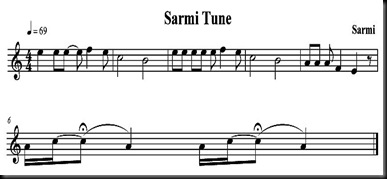

The Kauwerawet songs denote four characteristics. Their songs use a pentatonic scale, the melody descends the scale, lower key notes end their melodies, and the lyrics use parallelism.

In parallelism, the spelling and sounds of initial words of two lines are identical but differ in their last words. The beginning words of each line can be pairs and form the same or second word repetitions. In another case, a single polysyllabic word is different at the beginning part of a line but shows identical spelling and sounds at the ending part of the line.

Parallelism

Not only the lyrics of Kauwerawet songs but also those of the Awembiak songs contain parallelism. The song entitled Yamo of the Awembiaks can explicate parallelism.

Naga naga dewi wowai

Dega dega duwa wowai o a o

Mugu naga lu ambagage o

Asiloe naga naga duwang wae

Each couplet of this type of quatrain contains parallelism. The first couplet has the pair of words naga-naga and dega-dega. Each word is a reduplication and has identical spelling and sound. In addition, the spelling and sounds of initial words in the second couplet, mugu naga and asiloe naga-naga, show parallelism at the word naga and its repetition. Parallelism is also present at the end of the first couplet: dewi wowai and duwa wowai. However, the word pairs at the end of the second couplet are different.

In other lyrics, an initial word pair does not sound identical at the beginning but at the end. This is particularly the case with words having more than three syllables, words that seem to be compound words. An example given by Kunst is based on a Kauwerawet song:

Mamakanane

Kerekanane

Vocalization

The o a o sounds in the Yamo lyrics resemble a musical interlude in the forms of vowel sounds that "fill in the vacancy" in the rhythm of a verse. These interlude-like sounds are similar to vocalization, that is, vocal sounds that fill in empty space in modern pop songs, such as o, oh, ooh, dooh, na, la, paparapap, and choochooa.

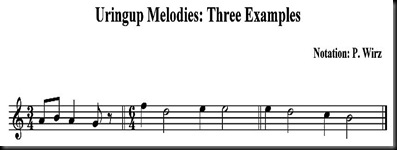

J. Kunst considers such interlude-like sounds as a "peculiarity". Dr. P. Wirz who noticed it tried to explain it based on the songs of other Papuan tribes who also used those sounds. During their singing, the words were not pronounced the usual way but were always ended with vocal sounds. Wirz presumed that this was an attempt by the singers to introduce rhymes. Besides, the words always ended with vocalizations affected by their melodies.

Other Characteristics of Central Range Songs

The songs of the tribes living in the Central Mountain Range of Dutch New Guinea are also known from other characteristics. What are they?

Rituals

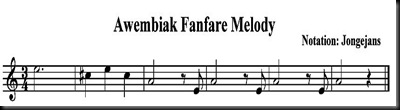

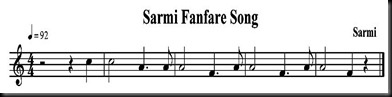

Their songs are connected to rituals. In particular, their fanfare songs are related to rituals.

Reduplications

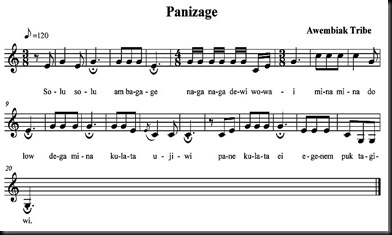

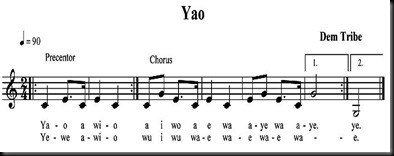

In addition, their songs make use of reduplications, seemingly for enhancing musical effects or beauty through the lyrics. A reduplication is a repetition of the same word. Some examples of reduplications in the song lyrics of the Central Mountain Range include solu-solu, naga-naga, mina-mina, dega-dega, wae-wae-wae-wae,we u we-we u we, and wi o-wi o.

Finger Clicking

They also accompany their songs by clicking or snapping their fingers. Such accompaniment seems to be rare in modern music.

It is not unique, however. Around 1958, Mr. P. Kanaar, a Dutch medical doctor working at the medical care and treatment quarter for lepers run by the Dutch Reformed Church Missionary in Manggurai (Wondama Bay), played a black-and-white movie for the Papuans gathering from various villages in the Wondama Peninsula in front of his house in Wasior, the little government town, at night. This event was part of the annual celebration of April 30, the birthday of Juliana, the Dutch queen at that time. The movie was about a group of black American musicians playing music. In a scene, they stopped playing their wind and brass instruments and instead clicked their fingers rhythmically in the air for some seconds before they continued playing their instruments.

Tremolo versus Vibrato

Interestingly, tremolo is also used in the singing voices of the Central Range tribes. This musical technique resembles vibrato in Western singing techniques.

In Western music, tremolo is a technique for melodic embellishments commonly used in instrumental music, such as string instruments that include the violin and guitar. In tremolo, two notes of different pitches are sounded rapidly and by turns. Usually, both notes form the second interval, such as doh-ray, ray-mee, mee-fah, or fah-soh.

The Central Range tribes who sang the songs studied by Western musical experts certainly did not know what tremolo was. To musically trained Western ears, it was a musical phenomenon that they identified as tremolo. This term indicates that there is a singing technique of the hinterland tribes that involves two notes that form the second interval performed rapidly and alternately.

Several Western experts in singing mistakenly use the term "tremolo" for what should actually be "vibrato". The succession of two notes in vibrato depends on their interval distance whereas the phenomenon of vocal music of the Central Range tribes should involve the interchange of the second interval. If this interchange was in fact aurally perceived by those Western musical experts, the term "tremolo" used by Kunst to identify that ornamental singing technique must be true.

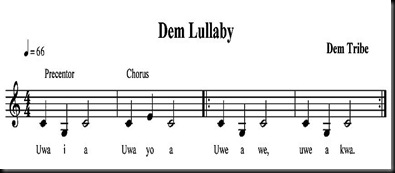

How did the Awembiak and Dem singers produce tremolo? They got it through the roots of their tongues, especially, when they sang long drawn out notes. If compared with vibrato, this singing technique reminds one of the so-called "throat vibrato".

Throat vibrato is not recommended in modern singing techniques. It is produced by manipulating the throat muscles to move the larynx rapidly up and down to create fluctuations in pitch. The muscular tension it causes results in a shaking tongue, jaw, and a shaking head. Throat vibrato often results in vocal fatigue and hoarseness.

Peculiar Sighs

There is still another singing technique typical of the hinterland tribes. Their singers interlinked the lyrical lines by peculiar sighs. These were produced by the sucking in of the breath. Some singers sucked in their breath while closing their eyes in an ecstatic state.

Rhythmic Diversity

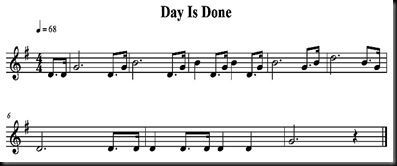

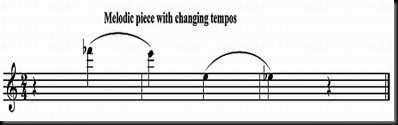

The Central Range songs indicate another characteristic: rhythmic diversity. This is particularly noticeable from their lyrics.

Lyrics are commonly formed from words and words from syllables. Words can have few syllables - from one to three syllables - or many syllables - more than three syllables.

The different numbers of syllables in different languages have been studied by linguists. On the one hand, there are languages rich in words consisting of many syllables and also in few (one, two, and three) syllables. These languages are monosyllabic because they have a lot of single-syllable words in addition to more-than-one and many-syllable words. English, for example, is a monosyllabic language. On the other hand, there are languages that are also rich in many syllables but poor in single and few syllables. These languages are polysyllabic because they have fewer single-syllable and few-syllable words in addition to many-syllable words. Indonesian, for example, is a polysyllabic language.

The monosyllabic or polysyllabic nature of a language is important in a song composition, particularly, in the composition of its lyrics. This characteristic affects the rhythmic and metric structuring of the song. The fewer syllables that form lyrics, the easier it is for a composer to structure the rhythm and meter of his song; the more syllables there are in lyrics, the more difficult it is for him to organize the rhythm and meter of his song. The difficulty of such structuring becomes evident when a translator of the polysyllabic Indonesian translates the lyrics of a foreign song in a monosyllabic language, such as English, into Indonesian. For the sake of congruence between the melodic and word accents, he will experience problems in ordering the rhythm and meter of his translation that involve polysyllabic Indonesian words to match the monosyllabic English words.

For the ease of ordering the rhythms and meters of songs, most composers, therefore, tend to use single-syllable or few-syllable words. These words are usually for conversations.

In its modern sense, the rhythm of a song can be said to be right if there is unity in the melodic and word accents. Unfortunately, a lot of Indonesian songs show conflicts between their melodic and word accents. A part of the lyrics and song, Burung Kakatua, already explained shows a conflict between both types of accents.

There are at least two presumptions about this conflict. First, the song composers do not know about prosody in music. Second, there are no standard rules about word accents in Indonesian. This lack results in the shifts in accents of polysyllabic words for various reasons, including the influences of vernacular languages in Indonesian and their typical intonations.

The shifts in accents on polysyllabic words can result in what Dr. J. Kunst termed "the rhythmic variability of polysyllables" in the lyrics of the Central Range songs. This phrase suggests that the languages used in the lyrics of the tribes are perhaps polysyllabic in nature. Furthermore, a monosyllabic word used either in one song or two different songs can undergo shifts in accents. For instance, the word nairoe - a four-syllable word - is pronounced through the recording with three different accents: na-I-ro-e, na-i-ro-E, or na-i-RO-e. The four-syllable word ambagage in two different songs is pronounced as am-ba-ga-GE in one text but as AM-ba-ga-ge in another text.

Note: Capitalized syllables indicating accents need to be read louder than others.

Even the few-syllable words undergo shifts in accents in the songs lyrics of those hinterland tribes. In one song, the researcher listened to the pronunciation of MI-na whose accent shifted to mi-NA in another song. In another song, a single-syllable word was uttered with two different accents: A-je and a-JE.

Why did shifts in accents occur in the song lyrics of the Central Range tribes? Kunst did not have the answer to this question. He only identified this linguistic phenomenon as rhythmic variability of polysyllabic words in those lyrics (and, occasionally, in the monosyllabic words of other lyrics).

End Rhymes

Not only did Kunst notice the shifts of word accents. He also paid attention to the rhymes in the song lyrics of the Central Range singers. A rhyme is a word that has the same sound or ends with the same sound as another word. In a song, the words have the same sound, especially at the ends of lines. End rhymes in songs are, therefore, words (two or more) that sound the same at the ends of lines.

What are the end rhymes used in the songs of the mountain tribes in Dutch New Guinea? In one song, the end rhyme appears as the same vowel sounds at the ends of three words: wowai-ujuwi-ragiwi. Another song has a real end rhyme: asiloe has an end rhyme with naga-naga duwang wae. The same song, however, also shows an attempt to create a more primitive end rhyme because it is formed by the "stop-gap" vowel o in o a o and ambagage o.

Pleasant Sounding Words

Kunst did not shed some light upon the problem of letter and syllable combinations to produce pleasant (or unpleasant) sounding words in the lyrics of the Central Range songs. Pleasant sounding words enhance music, "sounds that are arranged in a way that is pleasant or exciting to listen to". This characteristic not studied by Kunst will be briefly explored.

The Yamo of the Awembiaks will be used as an example. For simpler understanding, the words of each line will be spelled as syllables and the number of the syllables in the same line are counted.

Na-ga na-ga de-wi wo-wa-i (9 syllables)

De-ga de-ga du-wa wo-wa-i o a o (12 syllables)

Mu-gu na-ga lu am-ba-ga-ge o (10 syllables)

A-si-lo-e na-ga na-ga du-wang wa-e (12 syllables)

What are their features?

If the "stop-gap" vowels or sound interludes are counted as syllables, the whole lyrics are formed from 43 syllables. The syllables that are formed from the combinations of consonants and vowels - such as na, ga, and de - total 32, around 74 percent of the total number of syllables used. The second largest number formed from a single syllable - all vowels - totals 9, around 20 percent of the total number. This number is followed by one single-syllable word formed from the combination of a vowel and a consonant - am - and 1 single-syllable word whose vowel is enclosed on either side by consonants: wang.

If the sound interludes in the second and third lines are taken out, each of the first three lines has 9 syllables. The last line that has 12 syllables can be considered as a variation of the previous lines.

If the vocalization sounds are excluded, the lyrics display an aabb rhyme scheme. The scheme is formed from the rhymes of the first two lines that end in the i sound - wowai, wowai - and those of the last two lines that end in the e sound - ambabage, wae.

The whole lyrics uses 12 different letters. There are 8 voiced consonants (b, d, g, l, m, n, s, and w) and 4 vovels (a, i, e, o). Vowels are always voiced.

How high are the frequencies of using the voiced consonants and vowels in those lyrics? From the highest to the lowest frequencies, the voiced consonants used are as follows: g 11 times, w 7 times, d 5 times, n 4 times, l and m respectively twice, and b once. The vowels used from the highest to the lowest frequencies are as follows: a 21 times, e and o respectively 6 times, and i 4 times. It can be said from this description that both the voiced consonants and vowels that vibrate the vocal cords when singing increase the musical quality of the lyrics.

To understand the quality of the pleasant sounds just explained, we should also understand two other aspects of the lyrics. First, their meaning; and, second, the reason for such letter combinations in the lyrics.

Unfortunately, no translation of the lyrics is provided. It is, therefore, difficult for us to explain their sound quality . We also do not know the specific rules in the art of composing lyrics among those Papuan mountain tribes, rules that establish the relation between letter choices and the beauty of word sounds. Kunst's works as one of our references do not provide us with the needed data.

Assuming, however, that the letters that form the words of Yamo evoke the same musical effects as those in Western music, we can try to understand them by using rules about their overall tone quality. This tone quality is limited to vowels. The Western art of singing distinguishes three types of tone quality: dark, neutral, and bright. Each vowel has a particular form and requires a specific adjustment of the lips, tongue, and palate. The dark vowels are formed by the depth of the larynx, with the back of the tongue in a low position. Vowels in English words such as owe, law, put, and moon have dark tone quality. The neutral vowels are produced with a neutral tongue position. Vowels in English words such as art, ever, ask, and under shows neutral tone quality. The bright vowels are produced with a wide position of the mouth and lips, requiring the back of the tongue to be in a high position. Vowels in English words such as eat, it, and ale suggest bright tone quality.

To apply those types of overall tone quality in Western singing to the tone quality of the Yamo lyrics, we need to establish the approximate pronunciations of the four vowels in Yamo as compared with those in English. The a in Yamo is more or less like the English a as in art, the e sounds similar to the English e as in ever, the i resembles the English i as in eat or it, and the o sounds like the English o in on. It is clear from this comparison and from the rules on Western tone quality that a, the vowel used with the highest frequency in Yamo, indicates neutral tone quality; it is followed by e, another vowel showing neutral tone quality. The o in Yamo suggests dark tone quality while i indicates bright tone quality. Qualitatively speaking, the four vowels used in Yamo evoke a dominantly neutral tone, followed by dark and bright tones.

Meaningful sound quality in modern poetry serves a means to unify form (word or line form) and meaning. In modern vocal music, this unification also involves the melody. This synchronization is based on a general rule: form follows function. If the words of a song function as means for worshipping ancestral spirits in a traditional ritual, the word and melodic forms are adjusted for supporting the function of the lyrics.

Nothing is known about the meaning of Yamo. It is therefore hard to explain whether the meaning of its words has a function supported by the letter forms, the syllables chosen, and the melodic form. Considering the letters and syllables that seem to have been deliberately chosen, we can say there seems to be a connection between the function of the lyrics - for a ritual - and the forms of words and melody chosen. Only a further study will tell us whether this presumption is correct or not.

Do the whole lyrics produce a pleasant musical effect? The remarkable number of voiced consonants and vowels used, the repetitions of vowels - particularly, at the ends of the first two lines - and the end rhyme of the words produce musical sound that I think is pleasant to the musical ears.

Partly Understood Language of the Lyrics

Surprisingly, the song lyrics of the mountain tribes in Netherlands New Guinea are partly understood. The words are "full of obsolete, corrupted or distorted words". G.A.J. van der Sande explicated the keen perception of Kunst by focusing on this aspect of songs of the coastal Papuans in the north. The language of the songs in the Humboldt Bay and Seka in the western part is probably from an ancient language. It is no longer used in daily conversations and is partly understood.

"Musical Stratification"

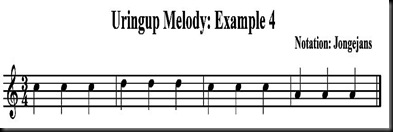

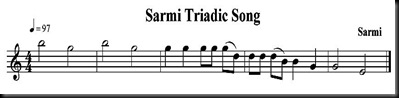

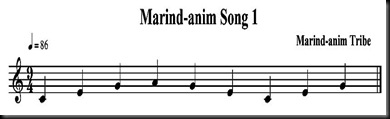

All those aspects and others of the traditional music in the Central Mountain Range that includes songs for rituals and ordinary songs indicate what Kunst termed "musical stratification". In other words, this vocal music implies layers of musical culture. In particular, the songs for rituals of the pygmy tribes in the Central Range are very similar to those sung by the people of the Karesau Islands, north of the present-day Papua New Guinea. These songs are formed by triadic notes, some of them result in fanfare songs.

Three Hypotheses

How is it possible that there are resemblances in the songs of the people living in two remotely located areas? Kunst forwarded three hypotheses.

Probably, the songs for rituals in the Central Mountain Range were inherited from one tribe to another. In the distant past, the Karesau people had inherited the songs for rituals to the highland tribes in Dutch New Guinea; some tribes living between Karesau and the Central Range were presumed to have possessed the same songs. "The cultural development of the mountain tribes, " Kunst wrote, "at least, seems to be perfectly homogeneous."

If the first hypothesis is not quite accurate, there is another hypothesis. Perhaps, the people of the Central Range and Karesau once had some contacts and lived together in the past. Through such communication, the triadic songs were inherited by the Karesau people to those of the Central Range.

If both hypotheses are not quite right, there is still another hypothesis. It is possible that the existing "fanfare" music of the Karesau and Central Range people points to another influence in the past. There was a particular civilization in the past that spread to a wider area. Later, that civilization was hit by various waves of a newer civilization. The fanfare music passed down by this civilization left an older musical layer which emerged to the surface and scattered over a wide area after it was "excavated" by Western musical experts, including Dr. J. Kunst from Holland. That musical layer was then engulfed by a newer musical culture from Melanesia and Australia and left a younger musical layer.

Three Important Questions

Which of the three suppositions is true? Before answering this question, Kunst said there are three important questions that need to be satisfactorily and comprehensively answered.

First, are the fanfare songs also found among other tribes living in and near New Guinea? Yes, Kunst answered. Fanfare songs are also discovered on Bougainville of the Solomon Islands, among the Karesau people, at the Tongara tribe, and at the Yabim tribe in Finschafen, all in Papua New Guinea. Those songs are noticed in the songs for magical practices in central New Ireland in the South Pacific.

Resemblances are also found in the song lyrics of those people from Papua New Guinea and those from the Central Mountain Range in Dutch New Guinea. The songs are characterized, for instance, by word duplications, finishing the lack of words for melodic phrases by using vocalization, the shifts in accents from one syllable to another in the same word, and the use of end rhymes at the ends of lines. An example of the last-mentioned feature is noticeable in the words wowai-ujuwi-ragiwi, each which ends in i.

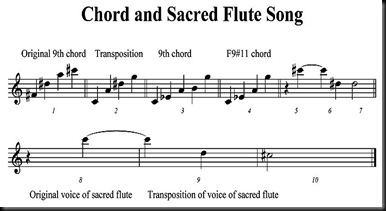

Second, which race or cultural agent should those fanfare songs be related to? Migrations could have been from the north or northeast of New Guinea. In addition, the fanfare songs of the Awembiak and Dem tribes could also be related to the wind instruments of the Bougainville people in the Solomon Islands. The people living here used a bunch of medium-sized thin bamboo flutes tied together by string. (Other bunches also found in other locations in Papua New Guinea and Dutch New Guinea consist of three, four, five, seven, or eight thin bamboos.) The end blown has evenly spaced round holes in a row. The other end is cut in such a way that the whole shape looks pointed at its lower end; the lower part of the row begins from the longest to the shortest flutes for sounding various tones. Such a bunch of flutes resembles the Western pan-pipes and are, therefore, called "pan-pipe flutes". The Bougainville fanfare songs were probably influenced by the tritones and their inversions played by the musicians there. The pan-pipe flutes, however, were also found in other places outside Papua New Guinea, particularly, in Merauke. Meanwhile, the fanfare songs are typical of the Karesau and Central Range people. Therefore, the flutes establish a relationship between the fanfare songs and pan-pipe flutes as the creation source of the fanfare songs because this type of vocal music is limited to the people of both regions. In other words, the connection between the fanfare songs in the highlands of Dutch New Guinea and the migration from Papua New Guinea are hard to be defended.

Third, are there any possibilities for discovering the causes of the fanfare songs. The possibilities exist.

If not from the Eastern direction, where did the influence on the fanfare songs in Karesau and Central Range come from? Probably, from eastern Asia, Kunst answered. The pan-pipe flute, he said, is a product from a highly developed civilization in eastern Asia. The flute is presumed to have been brought by mainland Asia tribes who migrated eastward in the past and entered New Guinea, probably, indirectly through islands in Papua New Guinea. Moreover, the pan-pipe flute remains a foreign element in the Melanesian musical culture; it has never been assimilated into Melanesian musical instruments. In addition, the flute is hard to be accepted as the creation source of fanfare songs of the Karesau and Central Range people. Their fanfare songs always have a ritual characteristic and the pan-pipe flute has never functioned as a sacred musical instrument nor has been used for rituals. As a general rule, traditional flutes in New Guinea are used for ritual purposes. Therefore, the influence of the pan-pipe flute of the Asian tribes that migrated to New Guinea on the creation of fanfare songs of the Karesau and Central Range people can be ignored.

The Origin of Fanfare Songs

Based on all the considerations already explained, Kunst proposed an argument for the origin of the fanfare songs in Karesau, Bougainville, New Ireland, and the Central Mountain Range. At the same time, his argument answered a previously posed question: How is it possible that there are resemblances between the songs of the people from two locations remotely separated from one another?

The songs could be a direct proof of a lower ancient layer of a common culture in those regions. The culture was a main civilization which in many places had been replaced by waves of a younger culture that overlaid it.

This ancient musical form had already existed side by side with a different and younger musical form. For the Central Range tribes, their fanfare songs were not affected by the pan-pipe flutes even though the flutes could be used to play triadic melodies. If this assumption is accepted, then the ancient music in the Central Range and in other regions in Papua New Guinea has been preserved until the 20th century and has been researched by Kunst and other musical experts. Those areas have been the most protected against the influx of foreign elements. (Perhaps, this is no longer the case nowadays.)

This song form could be considered original musical heritage of the Central Range Papuans. In this relation, Dr. P. Wirz who studied the pygmy tribes in the Swart Valley said clear traces of one of the oldest cultural layers from Australia and Melanesia, a negritic (of the negrito race) cultural layer, exist in the central part of Dutch New Guinea.

Higher Negritic Civilization

According to Kunst, this negritic culture can be called a primitive negritic civilization. From the musical point of view, however, this civilization is higher than the younger cultures that drove it to the hinterland. Musically considered, the fanfare songs of the Awembiak and Dem tribes in the Central Range are more advanced than the Australian type of songs - also found in the northern coast of Netherlands New Guinea - and are also more developed than most musical phenomena discovered during Kunst's period of visits in Netherlands New Guinea.

What kind of typically modern Papuan can be developed from that negritic culture? The last part of this series on the music of the mountain tribes in Netherlands New Guinea will answer this question.