There are two types of bamboo flutes known in Dutch New Guinea. The modern thin bamboo flute, not native to Papuan traditional music, has been used for probably more than a century. The traditional one is virtually nonexistent and is known only through scientific studies and missionary reports.

The Modern Flute Orchestra

The nine-hole thin bamboo flute used in a modern flute orchestra - particularly, along the northern, northeastern, and northwestern coasts in Netherlands New Guinea - is not a typical Papuan flute. It was probably introduced by Ambonese Christians to the Christian Papuans in those areas at the turn of the 20th century and has been used ever since.

One end of this flute is usually plugged up with a cut piece of gabah-gabah, the inside part of a dried stalk of a sago tree. A mouthpiece is drilled with a pointed iron bar heated with firewood close below the plugged up end. A few inches downwards, eight finger holes evenly spaced are also drilled with the same heated iron bar. Usually, no tuning fork or pitch instrument is used to measure any diatonic major key for the flute. Anybody skillful enough can produce a flute by using a previously made flute perfectly tuned as a standard pitch measurement. The other end of the flute is left open.

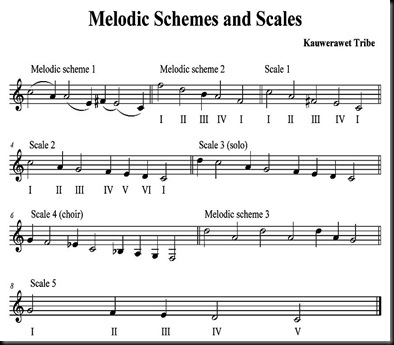

This modern flute can produce an octave of a diatonic scale. No chromatic tones can be played and heard from it.

One modern flute orchestra can consist of one small, thin bamboo solo flute with a high and piercing sound, similar to that of a Western piccolo. This flute leads the orchestra by playing the main melody. A large majority of the other flutes are of a medium size and are grouped into those playing the soprano, alto, and tenor parts. Another group consisting of large size thin bamboo flutes form the bass. Self-made drums that resemble the Western snare and bass drums used for marching complete with a pair of sticks (for the snare drum) and a mallet stick (for the bass drum) form the percussion section. The mallet stick is made from a piece of strong and round wooden stick ; one of its end used for beating the drum is wrapped with a special piece of clothes that can produce a deep, dark, rumbling bass sound, resembling that of a disco bass drum. Certain flute orchestra groups also use complete sets of commercial snare and bass drums used for military march music. In a 2/4 or 4/4 song, the bass-drum beats usually follow the meter, with some incidental variations. The snare drum is played in various rhythms, some of them improvised. A complete flute orchestra consists of at least seven players.

The songs played by a flute orchestra are of any types. They include church songs, modern folk songs, Western (including Dutch) march songs, and even self-composed songs.

Strange as it may sound, the church songs played are often of Anglo-Saxon origin. They include those mellow, sentimental, "bound-for-heaven" songs, and other lively, sunshine-bright songs.

This inclination was probably influenced by two hymn books that contain a lot of Anglo-Saxon church songs: Doea Sahabat Lama and Mazmoer dan Tahlil. Both were very popular before and after the Second World War among the Christians in the eastern part of Indonesia (West Timor, North Sulawesi, and the Moluccas) and in Netherlands New Guinea.

The harmony of the orchestra is usually formed from the Western diatonic music. It includes the tonic, subdominant, dominant (including dominant seven) and is sometimes varied with the supertonic, mediant, and submediant. The harmony usually follows parallel and similar lines: when the lead flute goes up, flat, or down in the main melody, the accompanying soprano, alto, and tenor flutes do the same or form similar lines. The bass flute usually plays the root notes of the chords or harmony. This type of harmony is also typical of both hymn books, also sung in four parts by both children's and adult choirs in church services or Christian festivities.

Harmony moving in such parallel and similar lines is not only easy to play. It is also easy to construct. Once a flute player understands and masters the ABC of such harmony, he can easily or spontaneously form the melodic line of his part that harmonically supports or embellishes the main melody.

Then, came Rev. I. S. Kijne (1899-1970), one of the most prominent missionaries of the Dutch Reformed Church Missionary in Dutch New Guinea. As a highly gifted musician, he taught his Papuan students modern church and selected secular songs from Continental Europe, Britain, and the USA by using a different system of harmony at the Christian Teacher's Training College for rural areas in Miei, an important village in the Wondama Peninsula, north Netherlands New Guinea, from 1925 to 1942. The harmonic parts of the songs are combinations of parallel, similar to parallel, oblique, in-unison, and contrary motion. He taught his Papuan students, later teachers at Christian three-year elementary schools in the rural areas managed by the Missionary of the Dutch Reformed Church in Dutch New Guinea, to teach Papuan pupils and their congregations to sing the "Kijne method": choirs should sing their songs by heart, the singing mouths should look oval to produce sonority, the right singing voice should be put in the right singing part, and the new harmony that also includes chromatic tones should be used.

The college is also the first teacher's training institute in the whole of Dutch New Guinea.

Before the Second World War, he published his translations into Malay (now Indonesian) of those songs he had taught at that college and some others in a hymn book entitled Mazmur dan Nyanyian Rohani (Psalms and Spiritual Songs). The spiritual songs include Beethoven's Song of Joy, G.F. Handel's melody for Daughter Zion, another melody for his Joy to the World theme, and J.S. Bach's O Sacred Head Now Wounded. A four-part edition for mixed choirs uses the modern harmony just mentioned. This hymn book containing only the main melody in the sol-fa notation plus lyrics is still being used by some main-stream Protestant churches in Indonesia, including the Evangelical Christian Church in the present-day Papua and West Papua provinces.

What not many of those who use Kijne's hymn book know nowadays is that he also published a special edition for a four-part flute orchestra in Dutch New Guinea. Because the flute players were familiar with the tonic sol-fa notation (the number or cipher notation), the edition used this notation system. It was not published again, however, when Netherlands New Guinea became a part of Indonesia in 1963.

Though the flute orchestra has been quite popular among the coastal main-stream Papuan Protestants in Dutch New Guinea since the turn of last century, the flute itself is not native to them. It is a foreign cultural element that nevertheless has enriched their musical heritage.

Traditional Flutes

How does the traditional flute in Dutch New Guinea look like? Why is it virtually nonexistent?

There are many types of traditional flutes in Dutch New Guinea. They are made from the thin and thick bamboos. We know them from scientific documents left by Dutch and other scholars.

Two of them, however, were commonly used in the northern coast. First, the small flute for giving signals used in Witriwai and Humboldt Bay. Second, the flute played by the Saberi tribe east of Apauwar River. One of its end is open and a part of the other end is covered by a cut hole at its joint. Both flutes are typical of both areas.

Uneven overtones

Can traditional flutes create harmonics? In other words, can they produce overtones in addition to the lowest or fundamental tone?

Dr. Kunst said the flutes did create fundamental tones but with uneven and even overtones. Their shapes, sizes, and how they were made and blown affect their characteristics of overtones. The two types of bamboo flutes already mentioned were described by G.A.J. van der Sande, a Dutch scholar.

One of them comes in various sizes. It is thin in relation to its length and is blown at its upper end; its lower end is closed by its joint or node. Because of its typical size, shape, and way of playing, it produces uneven overtones in addition to its fundamental tone.

Even overtones

The other type comes also in various forms and sizes. Compared with the first type, the second type is wider and shorter. It also has a round, oval, or square hole in the middle. Generally, the hole is closer to its closed end than to its open end. The size and shape of such a flute can produce even harmonics, but the larger diameter of the bamboo seems to obstruct more than one single tone.

The last mentioned flute is short and thick. The aerophonic instrument is played more easily than the thin, long flute.

The Sacred Flutes

The thin, long flutes are called "sacred flutes" because they were blown only during sacred rituals. Women were forbidden to see or watch or listen to them when they were blown.

Playing them was so difficult that not a single European, even Dr. Kunst himself, could blow one! His attempts even ended in embarrassing failures.

Only the sturdy, barrel chested, and mature Papuan men could blow them. Because the way a sacred flute was blown needed a lot of energy, the men able to play sacred flutes could only hold on for a short period of time, became quickly exhausted, and perspired. Van der Sande who witnessed the playing of the sacred flutes commented: "I have seldom seen a Papuan exerting himself more than in producing this sacred music."

The musical tones of the thin, long bamboo flute were carefully and accurately measured. Which harmonics was sounded? Attempts to determine the series of partials (overtones) failed, partly because the flute pitches were not based on Western harmonics and presumably the manner of blowing the flute also caused the failure.

Van der Sande determined the fundamental tone of the sacred flute with a cut hole at its joint at C sharp (#C). However, he determined its harmonics at A, C, and E; the overtones considered were uneven, caused partly by the stopped or closed end of the flute.

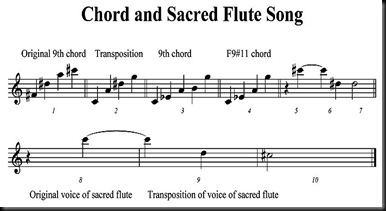

Chord 9

In spite of the problems of determining the harmonics, a part of the melody played on the flutes and recorded produces four tones that can be appreciated by Western musical ears. The tones "have a sweet organ-like sound". Not only that. The four tones even form "a true chord", the ninth chord sounded only by four tones. They sound familiar and quite pleasant to European ears.

In the C diatonic major key, the ninth chord of the tonic (C), for example, is formed from the C as its root or bass note. By going up step-wisely from the lowest tonic note, you meet D nine diatonic steps above C: C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D. According to standard rules of Western harmony, C9 is composed from C-E-G-Bb-D, with D as its highest note.

The sacred flutes that create the four tones indicate the voicing of a ninth chord. If this is a C9, there are at least two types of voicing. First, the selection of the tone sequence of C-E-G-Bb; or, second, the selection of the tone sequence of E-G-Bb-D.

Is the ninth chord detected in the sacred flutes the same as one of the tone sequences? Kunst noted down the ninth chord produced by the flutes as follows:

You can notice a practical equivalent for singing at "Transposition". The note sequence in this diatonic key in fact consists of four out of five tones of the F9#11 chord whose B tone is not used. From the lowest to the highest tone, the complete sequence of the ninth chord is C -Eb-A-B-G. The B note not used leaves four tones: C-Eb-A-G. If you reorder this sequence, you get the ninth chord sequence Kunst discovered from the sacred flutes: C-A-Eb-G. The Eb note that sounds exactly the same as D# can also be written as D#, making another possible four-tone chord: C-A-D#-G. (See "9th chord" and "9#11 chord".)

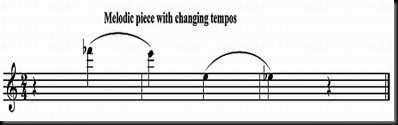

Changing tempos

In addition to the ninth chord, Kunst noted down the tempo of the song played on the sacred flutes as recorded by the phonogram. The tempo was measured on the basis of the number of tones played in one minute; he got sixty tones per minute.

Another recording indicates the development of different characteristics of the melody and tempo. The melody starts with "a soft indefinable tangle of sounds, a melodious whispering in the higher tones: the playing is fast, approximately 240 tones per minute. After that, there is a plaintive movement which is repeated several times" which is presumed to be the imitation of bird calls. The plaintive movement begins with a speed of 148 tones per minute, then increases to more or less 196 tones, and finally slows down again to 148.

The melody played is as follows:

The four tones are played on four different flutes. Two are long and the other two are short.

Why the Traditional Flute Disappears

Why is the traditional flute virtually nonexistent? There are many reasons.

Obviously, the modern life the Papuans in Dutch New Guinea experienced has been one of the causes of the disappearance of the traditional flute. The modern life resulted in the tendency, particularly, among the younger Papuan generation who were educated in modern schools established by the Dutch and managed under their supervision, to prefer modern music, including the modern flute orchestra. Sooner or later, the older Papuan generation who knew the art of playing the traditional sacred flutes and their related rituals based on myths died and, therefore, could not pass on their skills to the next generation. The younger generation in turn began to see their musical culture as being inferior and shameful to the modern one.

Perhaps, a more significant or enduring cause of the disappearance of the traditional flute came from Christianity. The flutes were strongly related to anti-Christian teachings. They were used in rituals based on myths that among others dealt with spirits of the ancestors and forest (trees, animals, and so on) and beliefs that were contradictory to what the Bible taught. Dutch missionaries who understood this challenge to the Christian faith sometimes used confrontational missionary methods to overcome this challenge. They tried to do away with the anti-Christian traditional culture, including traditional music, through persistent persuasion. Through such persuasion, they built negative images of the culture with its traditional music in such a way that the Papuans won to Christ abandoned their culture and music. Generally, the missionaries were successful in their efforts.

Such persuasion, however, was not forced by the missionaries into the Papuan perception of freedom, including their freedom in making the right choices. Rev. F.J.F. van Hasselt, Jr., a Dutch missionary of the Dutch Reformed Church Missionary assigned in Manokwari as the center of the missionary work in the northern part of Dutch New Guinea since 1855, is one of those who showed prudence and persistence when he tried to persuade the Papuans to leave their old ways of life and accept the new, Christian-based life.

He came at the time the Papuans - particularly, along the north-eastern, northern, north-western, and south-western coasts of Dutch New Guinea - underwent what might be called the Great Spiritual Awakening after the Gospel was brought to them in 1855. The awakening started on January 1, 1908 and spread like a "spiritual earthquake" from its spiritual "epicenter" on the Island of Roon, north of the Wandamen (Wondama) Peninsula in the southern part of the Geelvink Bay. Papuans from these areas came in masses - in scores, hundreds, and thousands - to a new era after they and their ancestors had lived on that western part of the huge island of New Guinea in the South Pacific for around 10,000 to 40,000 years. For aeons, they had been dreaming vaguely through their sacred myths of such a "golden age". The Biak-Numfor and a lot of other Papuan tribes had for millennia kept their mythical belief of the return of Lord of the Utopia, a Messianic figure, a mythical hero from the dim past who would bring Utopia, a kind of Welfare, Happy-Go-Lucky State to the Papuans. The Great Spiritual Awakening then made them aware that the expected Lord of the Utopia they had been dreaming about for so long was Nobody else than Jesus Christ and that the Utopia they had been yearning for during those aeons was nothing else than the Christian civilization!

The transition from the old to the new ways of life did not happen as dramatic miracles. The sober-minded Papuans frequently showed inner conflicts when faced with the consequences of abandoning their old, endearing tradition on the one hand and accepting Christianity as their new "tradition" on the other hand.

Van Hasselt, Jr. who understood their mind-set well and employed prudent and persistent persuasion came up with a solution acceptable to both biblical-based and Papuan logic. He came to them not as a "temple destroyer" but as a "liberator". As a liberator, the Gospel he preached to the Papuans was that of "openness, freedom, [and] emancipation", fundamental ideas understood and accepted by the Papuans.

In what specific cases did he not appear as a temple destroyer but as a liberator? There were some specific cases, but one will suffice in describing his role among the Papuans who sometimes wavered in choosing between the old and the new ways of life.

In 1910, he visited Masi-Masi in the Sarmi area, some hundred miles west of Hollandia (now, Jayapura). Darma, a traditional temple in which spirits of the ancestors were revered, was still standing. The dawet, the traditional sacred flutes, were still played in and around the temple. Van Hasselt, Jr. persuaded the Papuans to choose the church instead of the temple and the Christian God instead of the "demons" in that temple. The evil spirits in there would not make them smart but ignorant.

The Papuans finally came to a decision to let the temple be destroyed. At the missionary's request, around 100 sacred flutes in the temple were thrown outside the temple. They were brought to the house in Masi-Masi where van Hasselt, Jr. stayed. Then, came the destruction of the temple for demons. Since 1910, both the sacred flutes and the temple in Masi-Masi where they were kept and played have disappeared from that area.

When criticized for his role in the destruction of the traditional culture of the Papuans in Masi-Masi, he defended his decision to do so. He was not a temple destroyer; instead, he was a liberator of the Papuans from their old beliefs. He got strong support from influential Papuans, such as village and clan heads in Masi-Masi, to liberate the people from their old ways of life.

Difficult to Be Developed

Apparently, those traditional flutes are hard to be developed into modern flutes. The sacred flutes have limited mouthpieces and finger holes, it is extremely difficult to blow them, they are related to traditional beliefs, and have other limitations.

This does not mean that it is impossible to modernize them. Any creative musician, Papuan or non-Papuan, can modernize them.

What I think can be developed is the four-tone melody played on the four sacred flutes. The change of the melody, its atmosphere, and tempo can be recreated by using the tones as a melodic motive. A highly imaginative musician who understands Western music and its techniques thoroughly can compose modern songs using the four tones and make them sound typically Papuan.

Possibility for Development

A comparison with the development of the nine-hole modern flute can be made. So far, only diatonic tones of an octave have been played on the flute. The tones are produced through the correct lip position at the mouthpiece and the correct blowing of the flute. At the same time, opening one finger hole while closing others according to the tones of a melody produces a song. Such lip and finger positions, however, do not create chromatic tones.

Is there is a possibility to play chromatic tones on the modern bamboo flute? Yes, there is.

How? Assuming that the flute is tuned to the key of C major, a player can transpose the key from C major to G and D major and extend the melodic range to more than one octave. What he (or she) needs to do to get the chromatic tones is to partly open his fingers from the holes! The creation of chromatic tones will enable him to not only play songs having both diatonic and chromatic tones but also to transpose his first key to another key.

Such an improvement in tonal range and colors shows clearly the capability of the creative human mind to transcend what was previously considered unthinkable or impossible. The musical reality is not a rigid wall a musician cannot "batter down" through his creativity. Instead, this reality is like "rubber": it has a lot of creative flexibility in different dimensions.