The Kauwerawet or Takutameso tribe lives in the montain range near the bank of the Mamberamo River. Dr. J. Kunst undertook his research on its vocal music.

Two of its songs were recorded. Each has more than one version and was sung by four different tribesmen.

After recording both songs and their versions, Kunst and his colleagues made further study on them. They wanted to know which parts of the melodies could be considered the most fundamental and which were variations.

Various Musical Elements of the Kauwerawets

For that reason, they had a closer look at the various elements of Kauwerawet music. What elements?

Their songs were very short, each time sung with different words. For example, one song used three different texts, each with different words. The texts are given here in their syllabic and single-syllable word forms.

The first version: En-ce ma-ri-ri bo pi-ra-wa ri-ni-o /mak a ti bi-bi-dan. There are eighteen syllables: the first line has twelve, and the second line six syllables.

Ence, a bird hunter, came from across the sea. He was killed in the highland because of love. This is the only translation Le Roux provided from the Kauwerawet songs.

The second version: A-na ma-u ki-tau ki-ta ta ra mau /sab-a-ta bu-nu ki-ta. This version also has eighteen syllables: the first line has eleven and the second seven syllables.

The third version: En-ce bo-ya bo-ya, ko-bo ra-mak o so /tom a ko-ja sa-tu. There are also eighteen syllables: the first line has twelve and the second line six syllables.

Despite the same total number of syllables in the three versions, the words for each version are different.

The translation available from one of the versions does not help us understand the meaning of the other two. We, therefore, cannot determine whether each version is a different verse that supports a main idea or one that stands apart.

In addition, the text or words of the songs are strophic. The songs are, therefore, repeated.

Meanwhile, their meters are rather free. In other words, the songs are not so strictly controlled by one type of time signature, such as 4/4 or 6/8. Such meters of the Kauwerawet songs remind us of the Gregorian chants and psalms sung in Christian services that are also meter-free.

Furthermore, the number of syllables in a line is highly varied. In the three versions of one song, the numbers of syllables in both lines of the first and third versions are the same but those in the first and second lines of the second version are slightly different. In another example, the variations in the numbers of syllables of the lines of various versions of other songs are different. These variations obviously affect the rhythms of the melodies.

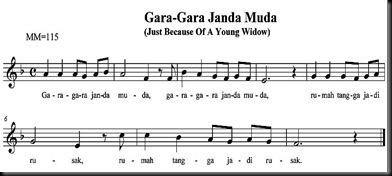

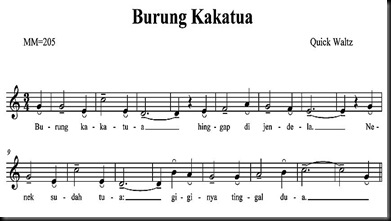

To understand further the change of rhythm caused by the addition or subtraction of the number of syllables in a line, I will add some words to the first verse of a Papuan folk song from the northern-coast tribes of Dutch New Guinea, composed in the diatonic major scale and entitled Gara-Gara Janda Muda (Just Because Of A Young Widow). The original lyrics and the number of syllables of each line are as follows:

Ga-ra-ga-ra jan-da mu-da, 8 syllables

ga-ra-ga-ra jan-da mu-da, 8 syllables

ru-mah tang-ga ja-di ru-sak, 8 syllables

ru-mah tang-ga ja-di ru-sak. 8 syllables

The English translation: Just because of a young widow, just because of a young widow, the married family falls to pieces, the married family falls to pieces.

In total, there are thirty-two syllables in this folk song. The same number of syllables in each line makes it not only symmetric but also determines the types and patterns of note combinations used.

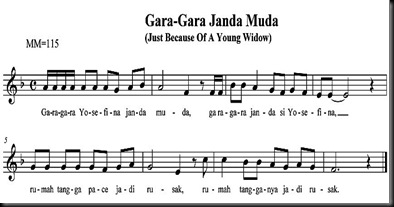

Now, the same lyrics will be modified by adding irregularly the number of syllables in each line, as follows:

Ga-ra-ga-ra Yo-se-fi-na jan-da mu-da, 12 syllables

ga-ra-ga-ra jan-da si Yo-se-fi-na, 11 syllables

Ru-mah tang-ga pa-ce ja-di ru-sak, 10 syllables

ru-mah tang-ga-nya ja-di ru-sak. 9 syllables

English translation: Just because of Josephine, a young widow, just because of Josephine, a young widow, the married family of the man falls to pieces, the married family of him falls to pieces.

Now, there are forty-two syllables that form the lyrics of this song but with irregular number of syllables for each line. In order to sing the additional syllables to the melody, a singer has to add some notes with different values to the original melody. The addition simultaneously modifies the rhythmic pattern of the song.

The expansion of the original lyrics of the coastal Papuan folk song - popular around the 1980s - explicates Kunst's discovery of the highly varied numbers of syllables in the lines of some song versions of the Kauwerawets. Such additions remind us of those in modern popular songs in which a solo singer sometimes adds words and therefore extra notes to an original song backed up by a duet, trio, or choir. The addition in a modern popular song however supports the main idea in the lyrics of the song.

What other typical characteristic is noticeable from the music of the Kauwerawet tribe? The imitation of bird voices woven by a singer into his song. When the recording was made, the imitation of bird chirps or twitters by the singer was not only woven into the song but also pleasant to the musical ears of the phonogram recorders. During the recording, the crow of a rooster and the natural quacks of ducks around the site for recording were even recorded and formed "natural" rhythm with the imitation of bird chirps or twitters by a male singer. Komasa, one of the male singers, was an expert in imitating bird songs.

Imitating bird songs was not only through the human voice. They could also be imitated by traditional musical instruments in other parts outside the area inhabited by the Kauwerawets, such as in the northeast coast of Dutch New Guinea. G. A. J. van der Sande, a Dutch researcher who joined an expedition to Netherlands New Guinea early 2oth century, observed the skills of the coastal people living in the Humboldt Bay in imitating bird songs through their sacred flutes. These are not the nine-hole bamboo flutes - thinner than the thick bamboo and with more space between two joints - used in modern flute orchestras, such as in church services. This bamboo flute probably originated from the influence of Molluccan Christians who brought it to Dutch New Guinea at the turn of the 2oth century; since then, the bamboo-flute orchestra has become a musical tradition among Papuan Christians. The sacred flute van der Sande noticed was made from a long piece of thin bamboo with more space between two joints. One of its end had a hole with a sliced circle that resembled the U letter; this part that was close to the end was carved with various motifs. The flute was sacred because it was used only in traditionally sacred rituals.

The Indonesian language distinguishes between "bambu" and "buluh" just termed "bamboo" in English. Both belong to the same plant family. The bambu, however, is thicker than the buluh and has less space among its joints when compared with that among the buluh joints.

A modern nine-hole flute is made of buluh. The sacred flute used in the Humboldt Bay as witnessed by van der Sande was also made from buluh.

Why were bird songs imitated in the traditional music of the people living in northeast Dutch New Guinea and of the Kauwerawets? Van der Sande presumed the birds whose songs were imitated through the sacred flutes in the Humboldt Bay were a part of the religious beliefs in their pre-Christian tradition. Based on van der Sande's presumption, Dr. J. Kunst also presumed that the bird-song imitation in the songs of the Kauwerawet tribe also originated from their traditional belief.

The technique of imitating animal voices in traditional songs in Papua was also observed among singers of the Pesechem tribe. It lives along the slopes of the southern part of the present-day Jayawijaya mountains. According to Kunst, however, the animal voices the Pesechem songs imitated through the Pesechem singers were intertwined and served as musical ornaments.

In fact, imitating animal voices has become a singing technique in some commercial music of the 20th century. It is apparent, for example, in the hoarse singing voice of a famous black-American trumpeter and jazz singer of the last century: Louis Amstrong. In some of his songs (such as Hello, Dolly), he imitated a voice similar to that of the growl of a dog or wolf - in short, a jungle voice - which was later known as "growl" in modern pop/jazz singing techniques.

Aside from the various jungle voices woven into traditional and modern music, Kunst's ears that were accustomed to European melodies perceived two distinctive characteristics of the traditional songs of the Kauwerawet tribe. First, they are short; and, second, they tend to descend the scale.

According to him, both indicate the earliest layer of Papuan culture. Both show primitive melodies equal to those of the Australian aborigines. Due to their identical cultural layer, the Kauwerawet melodies belong to the Australian (aborigine) type of music. Similar music was also discovered in the songs of the native islanders in the Torres Strait, between north Australia and south Dutch New Guinea. ". . . it is undoubtedly the most primitive music known at the present day."

What about the melody rhythms of the Kauwerawets and the tribes living in the Humboldt Bay as well as on the island of Yapen? The rhythmic patterns or forms of their melodies are simple. Some tones have small values followed by a tone sustained slightly longer, usually a low-sounding tone. The rhythm however can develop if the melody is accompanied by a text or words. The addition of the text can result in the combination of sixteenth notes, triplets, and quintuplets. The frequency of using triplets - each lasting for one beat in, for example, 4/4 songs - in Kauwerawet melodies was already observed in the traditional music of Papua New Guinea, later called Papua Nugini. The one-beat triplets are also heard in the melodies of the Humboldt Bay and Central Mountain Range tribes. Dr. J. Kunst himself listened to 6/8 songs containing triplets when he observed the songs of the singers from the Humboldt Bay and Yapen who took part in the Ethnographic Exhibition in Weltevreden - nowadays, Jatinegara (Jakarta) - in Batavia.

The use of triplets and quintuplets does not indicate typical rhythmic patterns of Papuan melodies. Triplets are also very common in the traditional melodies of the aborigines in Queensland (Australia) and in those of the Melanesians along the coasts of New Guinea as well as in those of the ethnic groups living in Nias, Sunda (West Java), and Flores in the former Dutch Indies.

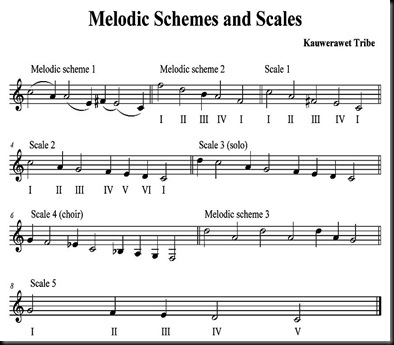

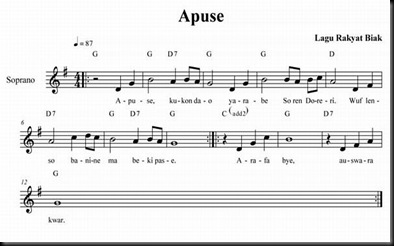

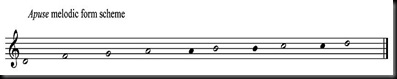

To understand the cores of such melodies to identify their nature in a nutshell, Kunst frequently used melodic form schemes. In particular, what are the melodic form schemes of the two Kauwerawet songs discussed at the beginning of this chapter and their versions? Kunst gave two notes on their schemes, with the second scheme as the most clearly identified.

The first and second melodic scheme shows the range of one octave. While the first starts and ends with its C tonic, the second begins and ends with its F tonic, rare start and ending in modern music. The downward movement of the melody is obvious from each scheme.

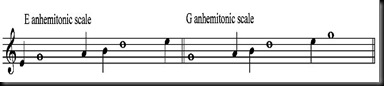

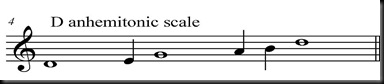

What are the scales then that underlie the melodic structures of both Kauwerawet songs? The first scale is composed of four main notes, one of them - the tonic (I)- is repeated. The second scale was an estimate from the results of three different recording. The E and D notes were estimated to exist in the scale.

The capital Roman numerals under each note of the three scale forms demonstrates the types of intervals used. The scale forms, however, are not based on Western major or minor scales; as a result, we may find it hard to apply whole tones and semitones in Western music to the three Kauwerawet music scales.

For example, the distance between the highest C and A notes in the second scale show a third interval (C-B-A) in the Western diatonic major C scale. According to rules in Western music, Roman numeral III should have been written under the A note. In the scale underlying the Kauwerawet melody, however, the A note is the second note after the highest C. Therefore, the A note forms a second interval with its previous C note. In short, it is the note sequence in that Papuan traditional scale that determines the type of interval used.

What types of intervals were frequently sung by the Kauwerawet singers? According to Kunst, the average intervals they sang include the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth intervals.

Another recording of Kauwerawet songs demonstrates a mixture of solo and choir singers. There are four male singers, one of them can be considered the solo singer whereas the other three form the choir also joined by the solo singer. The solo singer always sings the melody and three singers sing along at the key notes of the song.

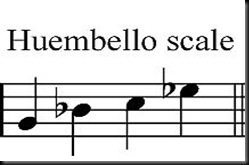

The third scale forms the basis for the solo song. Meanwhile, the scale for the choir uses the E and B notes, each of which is lowered to a semitone and becomes Eb and Bb. Both notes remind us of the blues notes in blues music in America.

The principal note for the choir begins from the first F note. It lasts until the second F note one octave lower. Based on Western musicology, the choir part, however, was added as a harmonic line to the solo scale by Kunst.

At the choir section, the voices of the four singers do not sound in tune. According to Western standards of good singing, the rhythm and melody in their singing are ragged, "untidy". However, they are in unison when they sing sustained notes. Kunst said their typical choir singing is an important characteristic of primitive music.

Another variation of one of the Kauwerawet songs results in another melodic form scheme and scale. The scheme is shown at the third melodic scheme. Its scale - the fifth scale -has the E note that seems to be suggested in the scale.

The Modernization of Kauwerawet Songs

The music of the Kauwerawet or Takutameso tribe belongs to the most primitive music. This category is known from three prominent characteristics: its melodies are short, they tend to descend the scale, and the choir singing is ragged. Their music, according to Kunst, indicates the earliest layer of the history of the Papuans.

In spite of these, some other characteristics of their songs can be traced forward to modern music, including that performed in Indonesia. Other characteristics are typical of Kauwerawet music and that of other tribes in Dutch New Guinea and Papua New Guinea. What characteristics?

- The song texts are strophic, a characteristic noticeable in a lot of modern songs influenced by Western music in Indonesia.

- There are slightly free meters in the songs. This tendency can also be noticed from psalm songs and Gregorian chants used in Christian services in Indonesia and abroad.

- The imitation of bird songs in the Kauwerawet songs and the playing of the sacred flutes in the Humboldt Bay seem to be connected to the religious beliefs of these tribes. For the Pesechem tribe, the imitation of animal voices is a musical ornament. In modern music of the last century, the imitation of animal voices, such as the growl in some of the songs sung by Louis Amstrong, reminds us of their primitive origin.

- Other characteristics of the Kauwerawet melodies include their brevity, tendency to descend the scale, and ragged choir singing. These characteristics are rare in modern music, except in short children's songs, "Amen" or "Hallelujah! Amen" songs in Christian services, commercial advertisement songs or melodies, and some disco songs.

- The typical rhythmic patterns of the Kauwerawet songs include different intervals and notes with different values, including triplets and quintuplets. In particular, triplets are also found in the melodies in the Humboldt-Bay, Yapen, Queensland, Melanesia, and Dutch Indies. Triplets frequently appear in modern music but quintuplets seem to be rarely used in modern music, such as popular music.

- The longest traditional scale known so far in Papuan traditional music has six notes. The shortest scale has four notes.

- The first to the sixth intervals are used in the scales. Rules about intervals for Kauwerawet melodies are different from those for Western diatonic music.

- The melodic form schemes for Kauwerawet songs are also typical because they are influenced by the scales that underlie them.

Obviously, there are some main characteristics of the melodies of the Kauwerawet and other Papuan tribes discussed so far. Some can be observed in modern music in Indonesia that are influenced by Western music. Others are typical of Papuan songs; they are not found or hard to find in modern music.

To enable Papuan ethnic music to be a part of the music of this century, professional Papuan and non-Papuan musicians have to modernize it. Life is change; therefore, the traditional Papuan music has to change, too. It has to be adapted to the musical trends of this century if it wants to become a part of modern music. Few people seem to like traditional music as it is. The majority, however, who are used to modern music will feel alienated from such traditional music. Therefore, Papuan traditional music has to be modernized, adapted to the demands of modern life.

How can Papuan and non-Papuan musicians modernize Papuan ethnic music with such characteristics? The following answers are subjective:

- Modernizing traditional Papuan songs should not eliminate their characteristics, including their typical features. Their elimination will make them identical with those of modern songs. Without identity, the modernized Papuan songs will lose their typicality and the chance for adding at least a new genre to the world music heritage.

- The recreation of traditional Papuan songs needs their modernization power from modern music, such as melodic and harmonic variations. Nevertheless, their typical marks have to be retained to strengthen their identity.

- Both secular and religious modern songs can be recreated based on the characteristics of traditional Papuan songs.

- The most primitive element of the songs can be emphasized by recreating it. The newly created music can express the primitive sides of man, such as his jealousy and tendencies for revenge as well hatred.

- To modernize Papuan ethnic music, musicians should be professional. They also need to show perseverance if they want to achieve significant results.